I thought it might be helpful to you to see the way in which the

Maccabean revolt is characterized by an expert in Seleucid history. The following excerpt from a book called

From Samarkhand to Sardis by Susan

Shermin-White and Amelie

Kuhrt uses the revolt to describe in more detail the formation of new political units in the Seleucid empire during the second half of the second century

BCE as the central power in Antioch withered and crumbled. These petty Hellenistic kingdoms for the most part modeled themselves after the imperial government they had managed to win

independence from. The

Hasmoneans were no exception. The narrative provided by I and II

Macc allows specialists in Seleucid history to look more closely at the manner in which new political entities in the empire may have emerged:

"An aspect of the Seleucid state in this period that has been given great, perhaps undue, prominence by some historians in relation to the question of its disintegration is the appearance of 'separatist states'; that is, parts of the empire, such as

Elymais, Persis,

Mesene,

Commagene and

Judaea apparently sought to establish separate, independent local dynasties, although the chronology of these secessions is not always clear. From the late 160s on, southern Babylonia seems to have split off under a ruler named

Hyspaosines who was probably the Seleucid satrap (Tarn 1938, 214; see above); similarly, in

Elymais Kamnaskires I (Strabo XVI 1,18; Tarn 1938,466) also became independent, possibly a little later at the time of the

Parthian conquest by Mithridates I (Le Rider 1965, 353-435; Frye 1984, 273). From some point either in the third or early in the second century a local dynasty of governors (

frataraka) ruled in Persis, but under the suzerainty of the Seleucid kings. Rather like

Kamnaskires and

Hyspaosines, they too seem to have become independent rulers only by c. 140 as a result of the upheavals caused by the

Parthian advance (Frye 1984, 159-61;

Wiesehofer 1986; 1988; in press; Koch 1988; cf. above pp. 30; 76-7). At an unknown date in

Antiochus IV's reign

Commagene, too, seems to have become a separate state under local rulers who gradually built the region into an independent

hellenistic kingdom using Seleucid dynastic names and drawing heavily on Iranian and Greek cultural traditions (cf.

Dorner 1975;

Colledge 1987, 158-9). Where the ultimate allegiance of such rulers was to lie depended inevitably on the power struggles between the

Parthians and

Seleucids. It is impossible to make any inferences, on the basis of the tiny bits of evidence for these moves, as to how Seleucid rule was perceived at this time within these regions.

The one area that is well documented in this respect is

Judaea, which throws light on the kinds of local complexities and rivalries that could arise in a subject community under Seleucid imperial rule. The central texts on which reconstruction of the events rests are I and II Maccabees, extremely hard to analyse because of their highly emotive, biased and even, at times, fictitious character. They reflect a later perception of the revolt against Seleucid rule as a 'Holy War' in which Israel stood alone against the massed hostile forces of the Macedonian and Greek world. They have therefore become a manifesto for the evolving history of Jewish orthodoxy and the definition of Judaism and Jewish identity - all of which has an importance quite divorced from the realities of the fairly small-scale local upheaval that the revolt really was. As with other communities,

Antiochus III, like other kings before him, had recognised and actively confirmed and supported the rights of the Jewish

ethnos to live under its own laws (the Torah) and social conventions subject to the usual Seleucid tax demands, as well as including hefty grants of immunity to leading sections within the community (cf. above pp. 51-2). It seems clear from Maccabees that a group, called by the text

Hellenisers (the exact meaning of which is unclear) and led by the high-priest Jason of Jerusalem, presented themselves as captivated by Greek culture and some typical Greek urban practices. They appear to have begun a move to turn Jerusalem from an

ethnos centered on the temple with its traditional cult into a

polis of Greek type and with a Greek dynastic name, Antioch (cf. above 183-4). They themselves approached the king,

Antiochus IV, and thought to have asked for city status, to which the king appears to have agreed - a fact of some interest since, by doing so, he revoked the policy of his father,

Antiochus III. In what way this movement resulted in some interruption and a temporary transformation of the Yahweh cult remains highly ambiguous and fiercely debated (

Bickerman 1937;

Hengel 1974; 1980;

Millar 1978), although the fact that it did so cannot be doubted. A group of pious Jews are presented as being outraged at the sight of their fellow-Jews exercising nude in the gymnasium and wearing new-

fangled clothes, such as the, to them, curious Greek hat,

thepetasos (I Maccabees 2.15; II Maccabees 4.7-14; cf. above pp. 183-4), and, of course, as horrified at the perversion of traditional religious practices. Firm repressive action, using military force, was taken by the Seleucid authorities against the aggressively orthodox rebels who attempted to impose their beliefs and

cultic conventions on the

Judaean peoples by brutal means. That this persecution of Jews by

Antiochus IV was limited to

Judaea and probably needs to be understood primarily in political, rather than specifically religious, terms is clear from a petition sent to

Antiochus by the Samaritans and granted by

him…One important outcome of this conflict was the emergence of the Ma

ccabee family as the secular and religious leaders of the Jewish Community, who eventually (in 129 under John Hy

racanus) founded themselves an independent dynasty closely modeled on that of the Seleucid kings (see above p. 138). It should be emphasized, against a widespread misconception, that the revolt of the Maccabees did not lead to the secession and independence of Ju

daea in 164 (cf., for sample, I Maccabees 10.1-9; 10.20; 10.59-60; 13.40); rather, what is striking is the way in which the later Ma

ccabee leaders prided themselves on their close relations with the Seleucid kings and how much they valued, and competed for the honour of being elevated to, the status of royal 'Friends' (cf., for example, I Maccabees 10.20; 10.89; 11.57-8). Only after An

tiochus VI

I's military defeat and death and the major loss of crucial territories, in terms of economic and military Resources, did Ju

daea come into being as an independent petty kingdom."

from

Samarkhand to Sardis p.224-8

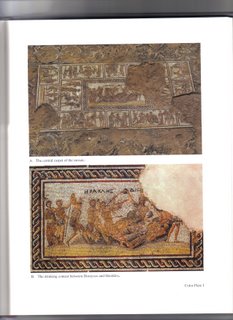

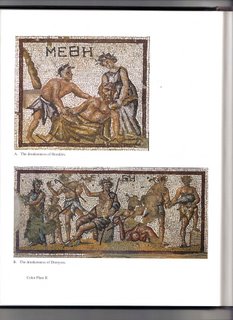

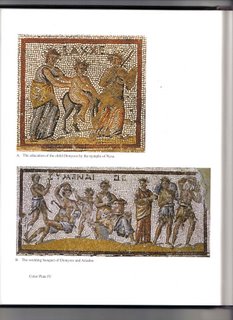

The following images come from a Roman style villa which was discovered in Sepphoris in the Galilee. The villa's triclinium, or dining room, was decorated with an elaborate mosaic depicting various scenes from the life of Dionysus, most notably a drinking contest between the Greek god and the often deified hero Herakles.We will discuss these images at length in class. Black and white reproductions of the images do not do these mosaics justice. Take a good look at the color scans of the scenes taken from the mosaic here and be prepared to discuss the images in class.

The following images come from a Roman style villa which was discovered in Sepphoris in the Galilee. The villa's triclinium, or dining room, was decorated with an elaborate mosaic depicting various scenes from the life of Dionysus, most notably a drinking contest between the Greek god and the often deified hero Herakles.We will discuss these images at length in class. Black and white reproductions of the images do not do these mosaics justice. Take a good look at the color scans of the scenes taken from the mosaic here and be prepared to discuss the images in class.

Here you see the depiction of Dionysus' triumphant arrival to the East. After Alexander's conquests in the 330's BCE the myth of Dionysus' arrival in India was often depicted in graphic form.

Here you see the depiction of Dionysus' triumphant arrival to the East. After Alexander's conquests in the 330's BCE the myth of Dionysus' arrival in India was often depicted in graphic form.