Matthew Platt

Ancient Jewish History

Loren Spielman

“Letter of Aristeas”

The, “Letter of Aristeas”, is the primary source for the compilation of the Septuagint, the Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible. Despite going on many tangents, it clearly portrays to the reader how the Septuagint came into existence. The story is portrayed through the eyes of Aristeas, presumably a Jew from Alexandria, Egypt. The letter is apparently a correspondence between Aristeas, and his brother in Palestine, Philocrates. Originally the text was written in Greek, however it was not written with the best grammar or style.

The letter opens with Aristeas greeting his brother Philocrates, telling him that he has tried to the best of his abilities to give him an accurate narrative of the events at hand. He continues to explain to Philocrates how a group had been gathered whose mission was the translation of the Hebrew Bible into Greek, something that they accepted upon themselves enthusiastically. He also mentions how he had taken advantage of this moment and had gotten King Ptolemy Philadelphus to release the Jewish prisoners of war that his father, King Ptolemy son of Lagos, had captured.

Aristeas tells of Demetrius of Phalerum who, on his selection as keeper to the king’s library, took upon himself the task of collecting all the books in the world. The king soon asked Demetrius about the completeness of his library, to which he answers, that news had reached him of a Jewish text that was worthy of inclusion into the library. Upon hearing this, the king asks what had stopped Demetrius from obtaining the Jewish text, to which Demetrius replies that there isn’t a Greek translation of the text, and that it is only found in the language of the Jews. After learning of this problem, the king soon writes to the high Priest of the Jews, Eleazar, asking for his help to finish this task. At this point in the narrative, Aristeas chooses to make his first tangent. He attempts to convince the king to release the Jews that had been exiled from Judea by the king’s father. As a way to persuade the king, Aristeas points out that the Jews will not only translate the text but also interpret it as well, and how they would be more willing to do so if there wasn’t such a large number of Jews in subjection within his kingdom. The king promptly releases not only the Jews that had been taken under his father, but also all the Jews that had been taken before and afterwards as well.

Once these exiled Jews were released, the king then asked Demetrius about the status on the translation of the Hebrew Bible. To this Demetrius responds, that although he had received a transcription of the Jewish books, they were translated somewhat carelessly and were not satisfactory for inclusion into the library. He goes onto say that this is most likely due to the fact that this translation didn’t receive royal patronage, and asks the king for permission to send a letter to Eleazar, requesting six men from each tribe, who understand Jewish law, so that they could decide on a translation that will be accepted by the majority, to which the king agrees.

The king writes another letter to Eleazar, telling him what he wishes to accomplish, and thanks him in advance as well as complimenting the Jewish people and the Jewish G-d. He names both Aristeas and Andrea of the chief bodyguards, Jewish men from Alexandria who were regarded as important, as part of the delegation to Jerusalem; he also offers many gifts to the Jewish Temple, something he continues to do throughout the story. Eleazar soon responds to the king, agreeing to all of the king’s requests, pledging not only his obedience but also his friendship. Aristeas then names all seventy two people that were chosen from the twelve tribes. At this point Aristeas goes into another digression, now explaining the details of the gifts given to the Jewish temple, by the king.

From one topic Aristeas then jumps to another, explaining his journey to Jerusalem, which he gives in great detail. When he finally comes back to the subject of the translation, Aristeas explains that the men chosen were all well versed in both Hebrew and Greek texts, but immediately he is side tracked yet again. He goes into a lengthy description of a discussion that he had with Eleazar the High Priest. When Aristeas finishes his story, he then discusses the arrival of the Jewish delegation to Egypt. How the king received the delegation at once, which was not the custom of the kings court. This showed the great respect that the king had for both Eleazar and the Jewish people. The delegation had brought the king a gift, a copy of the Law written on fine skins in Hebrew.

The king then, in a course of seven days, asks each member of the delegation question concerning a wide variety of topics. He, as well as the gathered assembly of philosophers, is impressed with the answers that the members provide. This is especially notable; when it is pointed out that they answered the questions almost instantly. According to Aristeas, three days later Demetrius took the delegation and showed them their rooms, and gave them anything that they needed in order to finish the task. After seventy two days, the delegation finished the translation of the Hebrew Bible; something that Aristeas points out was miraculous in its own right. The Jews of Alexandria then proceeded to place a curse on anyone who dared to change this translation in any way, due to the fact that all the members had agreed upon this translation.

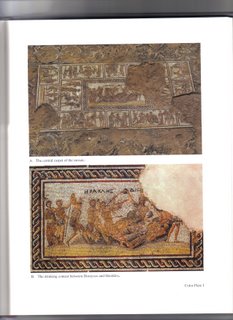

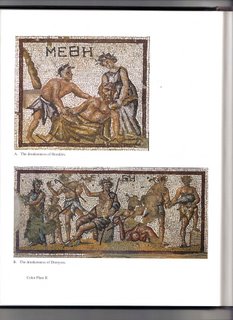

The following images come from a Roman style villa which was discovered in Sepphoris in the Galilee. The villa's triclinium, or dining room, was decorated with an elaborate mosaic depicting various scenes from the life of Dionysus, most notably a drinking contest between the Greek god and the often deified hero Herakles.We will discuss these images at length in class. Black and white reproductions of the images do not do these mosaics justice. Take a good look at the color scans of the scenes taken from the mosaic here and be prepared to discuss the images in class.

The following images come from a Roman style villa which was discovered in Sepphoris in the Galilee. The villa's triclinium, or dining room, was decorated with an elaborate mosaic depicting various scenes from the life of Dionysus, most notably a drinking contest between the Greek god and the often deified hero Herakles.We will discuss these images at length in class. Black and white reproductions of the images do not do these mosaics justice. Take a good look at the color scans of the scenes taken from the mosaic here and be prepared to discuss the images in class.

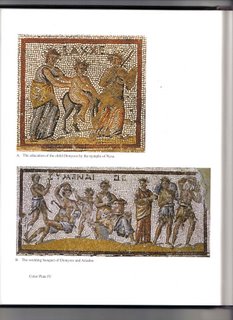

Here you see the depiction of Dionysus' triumphant arrival to the East. After Alexander's conquests in the 330's BCE the myth of Dionysus' arrival in India was often depicted in graphic form.

Here you see the depiction of Dionysus' triumphant arrival to the East. After Alexander's conquests in the 330's BCE the myth of Dionysus' arrival in India was often depicted in graphic form.