The following images come from a Roman style villa which was discovered in Sepphoris in the Galilee. The villa's triclinium, or dining room, was decorated with an elaborate mosaic depicting various scenes from the life of Dionysus, most notably a drinking contest between the Greek god and the often deified hero Herakles.We will discuss these images at length in class. Black and white reproductions of the images do not do these mosaics justice. Take a good look at the color scans of the scenes taken from the mosaic here and be prepared to discuss the images in class.

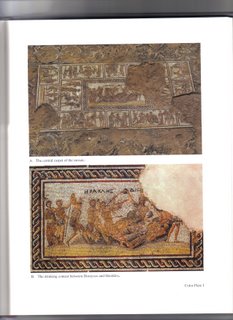

The following images come from a Roman style villa which was discovered in Sepphoris in the Galilee. The villa's triclinium, or dining room, was decorated with an elaborate mosaic depicting various scenes from the life of Dionysus, most notably a drinking contest between the Greek god and the often deified hero Herakles.We will discuss these images at length in class. Black and white reproductions of the images do not do these mosaics justice. Take a good look at the color scans of the scenes taken from the mosaic here and be prepared to discuss the images in class.The first panel above shows the overall plan of the mosaic.

The second panel is a close up of the center of the mosaic- the drinking contest between Dionysus and Herakles.

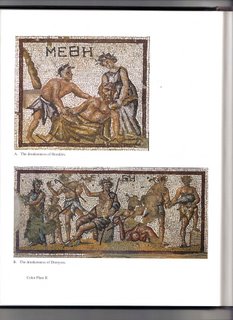

The top panel here shows Herakles in a drunken state. The bottom panel shows Dionysus under the influence. Both panels have the word "drunkeness" written as a superscription in Greek.

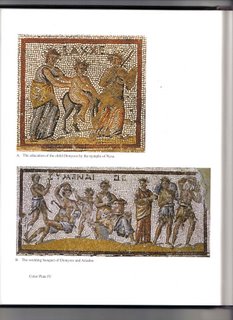

These scenes depict more scenes from the life of Dionysus; his education at the hands of nymphs, here called Bacchai, and his wedding to Ariadne, the daughter of Minos who helped Theseus escape the maze of the Minotaur. Theseus abandoned her on the island of Naxos where she was discovered by Dionysus.

This is perhaps the most famous image from the Sepphoris mosaic, sometimes called "the mona lisa" of Sepphoris. There is little identifiable iconographic significance to this particular picture. Rather, it shows the technical quality of the mosaic which rivals that of contemporary mosaics from the Roman villas in North Africa.

The bottom panel shows a scene from the childhood of Dionysus. He is being bathed by nymphs who were responsible for his early education.

Here you see the depiction of Dionysus' triumphant arrival to the East. After Alexander's conquests in the 330's BCE the myth of Dionysus' arrival in India was often depicted in graphic form.

Here you see the depiction of Dionysus' triumphant arrival to the East. After Alexander's conquests in the 330's BCE the myth of Dionysus' arrival in India was often depicted in graphic form.Dionysos was, among other things, the god of wine. Perhaps this explains the incorporation of a depiction of three lenobate or "grape-treaders."

Having looked at these images, who do you think lived in the villa at Sepphoris? Can we say anything about them? What was their religion? How wealthy were they? What were their interests? What was their attitude towards Greco-Roman culture?

The answers to these questions (if there are any at all) are more complicated than you might at first assume.